by Robert Fisk, Independent (London)

Holocaust expert Israel Charny’s new book makes uncomfortable reading, as he asks us to examine ‘a truth we haven’t faced fully enough’

September 25, 2018 – Confronted on a warm, soft Jerusalem evening by one of Israel’s venerable Holocaust scholars – and a psychologist to boot – a visitor to Israel Charny’s retirement home should perhaps keep a certain silence, especially if the new arrival is a journalist.

Charny, author of the monumental Encyclopedia of Genocide – and much hated by the Turks who are outraged by his conviction that the 1915 Armenian genocide was a reality – speaks with the low, rather pondering voice of a US east coast academic. Not unlike the great Noam Chomsky, I note injudiciously. The American linguist and philosopher is a hero of mine, but a rather less prestigious figure in Charny’s eyes. “God forbid!” announces the 87-year-old head of Israel’s Institute on the Holocaust and Genocide in Jerusalem. “You don’t know this – but I lived at the Chomsky house, as an undergraduate.”

He flourishes his most recent book, The Genocide Contagion, which asked readers to reflect on their own reaction to a future genocide in their own lives. It makes uncomfortable reading.

In today’s world, Charny says – slowly, carefully and with little forgiveness of us humanoids – he can see no “concerted political or culture-wide consciousness to take care of people”. On the contrary, “what I see is another replay of a truth that we haven’t faced fully enough. And this is that the human species – with all of its beauty – is a horrible, uncaring, destructive species that has delighted and excelled in the taking of human life for centuries. And there is no real addressing of this issue in our evolution that I know of.”

Is this an expression of the inevitable, I ask myself? And older man throwing in his hand after the iniquities perpetrated against his own Jewish people? I think not.

“The problem, in my judgement,” he says, “begins with our failing to understand that in the creation of our species and in the very original equipment that we come from, there are two parallel instinctive streams that are operating simultaneously. One is all those beautiful, caring, creative [things] – the art and the music and the philosophical ingenuity and the brilliant creativity – but it’s an utter mistake for us to pretend that that’s the end of the story, [that] that’s what humans really are.

“Because there’s another, no less powerful stream that includes killing off the next guy in self-defence – and self-defence means what you perceive to be self-defence, because that’s a whole big quicksand in its own right. It includes killing off the next guy – your brother – like the Bible begins with Cain and Abel, and it continues with a whole bunch of brothers who can hardly say ‘brother’ to one another, because they are really out in a deeply competitive readiness to overwhelm and even destroy the said brother. And it continues that way through all the identity systems that we have: religion, nationality, ethnic identification.”

Talking to a Holocaust expert, there are two subjects, of course, that cannot be avoided: the destruction of the Jewish people, and death. Charny does not appear to have forgiven Chomsky’s spirited but injudicious defence of the right to free speech of a French Holocaust denier who reprinted an essay on freedom of expression by Chomsky (without the latter’s permission) back in the 1970s. Chomsky, five years Charny’s senior, is no Holocaust denier. I prefer to avoid this elderly debate. Charny will later grumble about Chomsky over dinner.

But Charny’s constant defence of the Armenian people’s right to refer to their own people’s slaughter by the Turks as a genocide – and his repeated condemnation of the Israeli government for failing to use the word about the Christian Armenians of 1915 – is a mark of his uniqueness.

The work of Charny’s organisation covers Rwanda, as well. And Bosnia. And, after years of reporting Armenian scholarship on the genocide and Turkish denial, I am a member of the Jerusalem institute’s international committee. Talk to Charny about death, and his reply covers a host of armageddons. His long, perfectly formed response, deserves an equally long paragraph.

“Because there’s another, no less powerful stream that includes killing off the next guy in self-defence – and self-defence means what you perceive to be self-defence, because that’s a whole big quicksand in its own right. It includes killing off the next guy – your brother – like the Bible begins with Cain and Abel, and it continues with a whole bunch of brothers who can hardly say ‘brother’ to one another, because they are really out in a deeply competitive readiness to overwhelm and even destroy the said brother. And it continues that way through all the identity systems that we have: religion, nationality, ethnic identification.”

Talking to a Holocaust expert, there are two subjects, of course, that cannot be avoided: the destruction of the Jewish people, and death. Charny does not appear to have forgiven Chomsky’s spirited but injudicious defence of the right to free speech of a French Holocaust denier who reprinted an essay on freedom of expression by Chomsky (without the latter’s permission) back in the 1970s. Chomsky, five years Charny’s senior, is no Holocaust denier. I prefer to avoid this elderly debate. Charny will later grumble about Chomsky over dinner.

But Charny’s constant defence of the Armenian people’s right to refer to their own people’s slaughter by the Turks as a genocide – and his repeated condemnation of the Israeli government for failing to use the word about the Christian Armenians of 1915 – is a mark of his uniqueness.

The work of Charny’s organisation covers Rwanda, as well. And Bosnia. And, after years of reporting Armenian scholarship on the genocide and Turkish denial, I am a member of the Jerusalem institute’s international committee. Talk to Charny about death, and his reply covers a host of armageddons. His long, perfectly formed response, deserves an equally long paragraph.

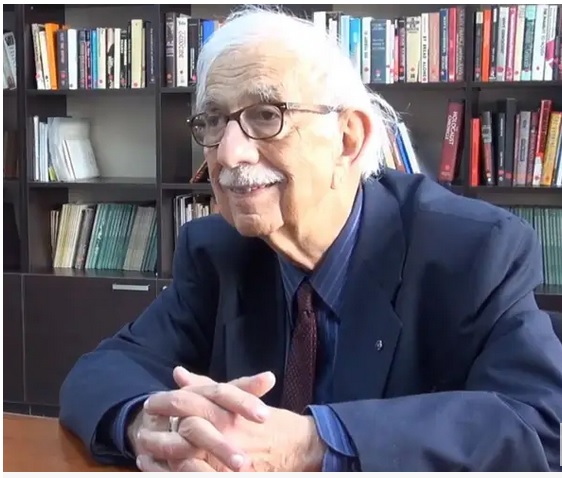

Charny’s constant defence of the Armenian people’s right to refer to their own people’s slaughter by the Turks as a genocide is a mark of his uniqueness (YouTube/Scholarm Armenia). This photo is taken in the Israel W. Charny Room at the Armenian Genocide Memorial Institute and Museum in Yerevan, Armenia.

If you look at the work of [Israeli-American psychologist] Daniel Kahneman and the works of some others,” he says, “you find endless evidence and analysis of how the human mind is capable of creating any piece of nonsense – imbuing it with authority, establishing it with factuality – when it is all, in the words of a great leader of the whole movement, to disestablish any hold that we might have had on [our] perception of reality and tests of reality, and the use of scientific method in thinking and in observation. For him, whatever his impulses call for, this is what reality becomes. And he then endows that reality with superlative adjectives – ‘is the greatest ever’, ‘there’s never been anything so great as…’ – whatever the heck it is.”

We have moved, of course, into Trump-world. I remark that the US president (Charny agrees he should be in a lunatic asylum) had used the word “beautiful” about weapons he was selling to an Arab Gulf state, and that large numbers of government officials travel to arms fairs around the world. “And sometimes,” Charny says, “you see their eyes looking at it as if it is an erotic object – such an attraction, such an excitement, such a wish to touch and use and express oneself through the Trumpian instrument.”

He asks if I know of Israel’s arms sales. “It sold to Rwanda during the genocide and it sold to Serbia during the genocide of the Bosnians. I have a very dear friend, [Israeli historian] Professor Yair Auron, who together with a wonderful attorney by the name of Etai Mack, have sued the Israeli government for information about both of those arms sales and they sued under a law that calls for release of information by the government when it is demanded.”

The script, as Charny put it, was as follows: “They get to court. The judge asks them to present what they’re after. The judge then calls on the representatives of the [Israeli] government. A government representative says: ‘Your honour, this is a matter of high security – can we see you in chambers?’ The judge takes them into the nearby judge’s chamber. They emerge 20 minutes later, and the judge says: ‘Case dismissed’.” This has happened to them [Auron and Mack] twice. It’s clearly built into the whole system.”

So what should people – us – be ready to do when witnessing the act of genocide? “To do everything they possibly can to save human life – their own and others,” says Charny. But he fears that the persecuted, while they may receive aid, will not receive military help. In the Holocaust, “there was absolutely no help, and even in those cases where there was some degree of cooperation with partisan fighters, it was limited, it was ambivalent, it was short-shrifting, mainly [in] the Soviet Union.” The RAF did not follow Churchill’s wish to attack the Nazi extermination camp rail yards.

“The Americans weren’t much better – not at all. There is a guilty conscience in the [western] relationship to Israel. I’ve never perceived it as being a conscience about ‘what we did not do to help’. I’ve perceived it as a kind of western sympathy with the people who have been so bitterly oppressed and decimated. But let’s test the question of conscience by looking at the world in its responses right now to places where mass murder is taking place – of the extent of intervention, the extent of caring – as reflected in the media. How would you rate it? That’s a rhetorical question.”

Reprinted in California Courier, January 4, 2019