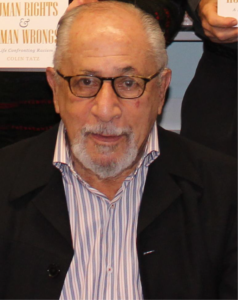

Colin Tatz of Sydney, Australia was a dear and esteemed colleague in genocide studies for many years. He was, for me, a clear thinking, decent, rational, and very constructive thinker and leader. As a Jew, I also appreciated and enjoyed with him his loving Jewish identification and fine ethnic humor – in general, he was a person who was fun to be with even as we dealt with serious topics of genocide, but of course our true bond was in the absolute commitment to the universality and oneness of all humankind. Colin Tatz’s major work over many years was indeed about the powerfully underprivileged Aboriginal minority of Australia. The following is an obituary selected by his dear wife, Sandra Tatz, for publication on our website at this time.

***

THERE ARE A LOT of teachers in the world who are admired or respected by their students, but it takes a pretty special teacher to be truly loved. Professor Colin Tatz was one of them.

We loved his sense of humour and his generous imparting of wisdom; we felt at home sharing a meal, or coffee and cake, at his and Sandra’s dining table, accompanied by engrossing conversation or career guidance.

We loved that Colin was a rebel with a cause. His rebellious streak was as endearing as it was genuine. He never shied away from taking on the orthodoxy – on suicide, on Aboriginal history – and calling things for what they were. He would never stay silent in the face of injustice, no matter the consequences.

Colin was a father, a ‘zeida’ and a husband, and those precious, private aspects of him belong only to his family. To them, and to history, we offer these thoughts about the legacy he left in younger generations through his role as a teacher and mentor.

Meher Grigorian*

Professor Tatz was one of those rare individuals who left an indelible mark on others. He certainly did with me.

As a final year undergraduate student at Macquarie University in 1997, I was in his thrall. His lectures were a masterclass in how a speaker should engage with their audience – intellectually, morally, emotionally. Professor Tatz didn’t just communicate the facts about the Holocaust and other great crimes. He exuded an uncompromising intolerance of such injustice.

He struck a primal chord in me as a young Armenian.

Throughout my upbringing, I had imbibed a sense that the world had forsaken us – our ancestors had been murdered, our homeland stolen, our monuments razed and our place names supplanted. And instead of an apology and redress from the perpetrators, there was unrelenting denial, placated by an uncaring world that had long since moved on.

But here was a non-Armenian who cared, who laid bare my own history and railed against those who sought to pervert it. Through his example, I undertook to delve into the suffering of other groups, while still prosecuting my own people’s plight. And he showed me the value of collaboration – of opening one’s heart and mind to others, and supercharging activism through building like-minded coalitions.

Professor Tatz was the most righteous and inspiring man I have ever known. I will forever cherish the time I had with him.

Nikki Marczak*

Colin mentored me like he was teaching me to ride a bike. He held on to the back of my seat as long as I needed and then when he judged I was ready, he’d give me a little push and off I’d go, cycling on my own. Then I’d turn around and cycle right back to show him how well I’d done, and he’d celebrate my achievement as though he’d had nothing to do with it. But I’d never have been able to do it without him.

We had the “Jewish connection” – a feeling of being understood and understanding – but he was never Jewish-centric. He was a true believer in human rights who fought against all racism and persecution. He always had a Yiddish saying that fitted the circumstances perfectly: emailing a tardy colleague with the subject line “Nu?” or making me laugh about a frustratingly lengthy publishing process by likening those responsible to a Hanukkah dreidel: “That’s what these people do! Spin around, from side to side, then droop.”

Compared with Colin, though, we were all “dreideling around” – not one of us, even those many decades his junior, could keep up with him. In an email exchange in 2016, Colin told me he’d begun a new book (which ended up as Australia’s Unthinkable Genocide) and had completed three chapters in three weeks. Responding to my admiration of such rapid work, he wrote, “When you get to my age and state of health, you know there is only today, and so today it has to be written.” It was a philosophy he lived up to the very end of his life.

Colin Tatz taught by example. He taught us to be brave; to stand up; he modelled solidarity and encouraged us to challenge our own views and the views of others.

His penchant to speak truth to power was a recurring theme among the memories shared by colleagues and family at his funeral and minyan on Sunday 24 November 2019. For example, Professor Konrad Kwiet, Resident Historian at the Sydney Jewish Museum, told those gathered that while academics are typically afflicted with a broken spine when forced to confront their paymasters, Colin had no qualms in telling university management what he really thought!

His principles were his principles, something to be fought for and never compromised, irrespective of potential repercussions. We hope that we inherited even a fraction of his courage.

We write today in grief but also in celebration of a man whose legacy will live on in all of his students. In us, a group of people who have been taught by Colin in different ways, but with the same core values, his memory will endure, and his influence will grow and thrive.

* Nikki Marczak is an Australian genocide scholar and survivor advocate, and a member of the Australian Institute for Holocaust and Genocide Studies. Meher Grigorian is a founding member of the Australian Institute for Holocaust and Genocide Studies