by Joe Levine

Retrieved from Teacher’s College at Columbia University. https://www.tc.columbia.edu/articles/2019/january/driven/

The Nuba

Betwixt, Between and Mostly Ignored

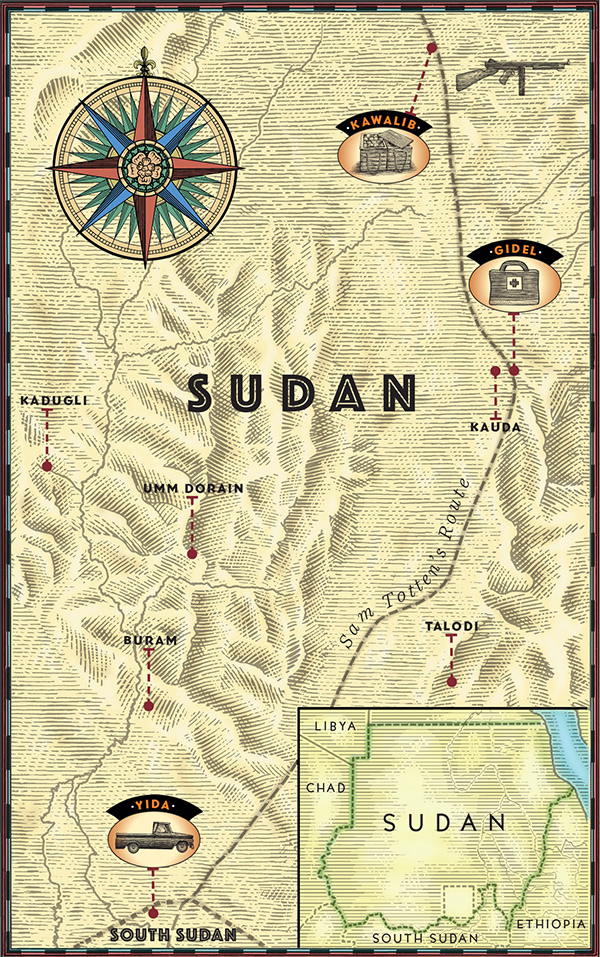

Sudan, Africa’s third-largest nation, won independence from Great Britain in 1956, but has been the scene of two subsequent civil wars between the primarily Arabic, Islamic north and the black African and Christian south. Though located in the north, the Nuba — a group of some 50 indigenous peoples — sided with the south, and endured repeated scorched-earth bombing campaigns that caused mass starvation.

Yet when the Republic of South Sudan won independence in 2011, the Nuba were excluded from a referendum that would have allowed them to join the new country. The Sudanese government of Omar al-Bashir has since conducted several additional bombing campaigns against the Nuba while barring all international aid organizations.

Sam Totten has sought to bring international attention to this little-known region, whose plight he charges has been ignored by both the United States and the international community.

Two years ago, on one of his many trips to deliver food to besieged civilians in Sudan’s Nuba Mountains, the genocide scholar Samuel Totten (Ed.D. ’85) was implored by a crowd in a village market to transport a wounded boy.

The only fully operational hospital with a surgeon lay 45 minutes away, through brutal heat and over jarring dirt roads. The route was vulnerable to aerial attacks by Antonov bombers that were exacting almost daily retribution against the indigenous Nuba for opposing Sudan’s president, Omar al-Bashir, in the nation’s decades-long civil war.

Totten, then 67, was practiced at sprinting for cover at the sound of an approaching plane, but recently the government had switched from slow, retrofitted cargo planes to Sukhoi fighter jets that appeared with virtually no warning. Two days earlier, in a town that he and his long-time Nuba driver and translator, Daniel Luti, had passed through, a Sukhoi missile had sheared a young man in half. Totten and Luti set off with the injured boy, his sister and family friends. When they reached the hospital, the boy — who had thrown a rock at an undetonated bomb — was dead. Totten drove the boy’s body first to his parents’ village.

“The father walked to the back of the truck, looked down at his son, and without a word…walked off into the field alone,” Totten writes in his book, Sudan’s Nuba Mountains People Under Siege: Accounts by Humanitarians in the Battle Zone. “When the boy’s mother saw [this], she let out an agonizing scream and fell flat on her face.” Later, when the mother remained in the truck weeping, “I reached out and touched her hand. She grabbed my hand, glanced up at me, and moved her hand a little higher, latching onto my wrist.”

Two days later, acutely dehydrated after delivering tons of food to the Nuba, Totten passed out, cracking his head against a cinderblock wall. He was taken to a Doctors Without Borders field hospital in South Sudan and airlifted to Nairobi Hospital in Kenya.

Actively Standing By

The spectrum in genocide studies runs from critical theorists, who argue for detached objectivity in order to scrutinize the field’s own biases, to scholar-activists, who focus on documentation to prevent further crimes.

And then there is Sam Totten.

Responding to an emailed query, The New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof calls Totten “a leader in galvanizing public opposition to genocides,” adding “I’ve been awed to see him sneak into the Nuba Mountains to bear witness to the bombings and deprivation. He’s the Professor Indiana Jones of genocide scholarship.”

Eric Weitz, Distinguished Professor of History at the City College of New York, says that “ideologically, Sam belongs to the school of putting himself in a hell of a lot of danger. He’s also the field’s community organizer, pushing the rest of us to take public stances.”

And Roger Smith, Professor Emeritus of Government at the College of William & Mary, says simply, “I’ve often wondered if he isn’t a saint.”

Not that Totten, Professor Emeritus at the College of Education and Health Professions at the University of Arkansas- Fayetteville and 2011 recipient of Teachers College’s Distinguished Alumni Award, isn’t scholarly. He’s co-founded a refereed journal and published a dozen books, delving deeply into Sudan’s ethnic, religious and political makeup.

Still, Totten, a tall man with a deep belly laugh, is far from being your stereotypical tweedy professor. He does what he does, he says, because he has “a visceral disdain for bystanders.” The real bystanders — “outsiders with the means and freedom to act — are never innocent,” he says.

“It’s easy to point fingers from afar at people living under a dictatorship and say, ‘They should have stood up to Hitler,’” says Totten, who served as the lead author of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum’s Teacher Guidelines for Teaching About the Holocaust. “Hutus [members of Rwanda’s majority ethnic group, which carried out genocide against the minority Tutsi] have told me that they were afraid to help anyone for fear their families could be killed. That puts things in a vastly different light.”

Totten speaks worldwide, is a frequent radio guest, writes constantly to reporters, editors and U.S. and U.N. officials, and publishes countless opinion pieces.

In 2004, he served on the U.S. State Department’s Atrocities Documentation Project in eastern Chad, interviewing recent survivors of the Darfur genocide. The Project’s findings — including a woman’s account (below, from Totten’s 2011 book, An Oral and Documentary History of the Darfur Genocide) of being gang-raped by members of the Janjaweed, the al-Bashir government’s proxy militia — prompted then-Secretary of State Colin Powell to declare that Sudan had indeed perpetrated genocide.

“There are so many people nobody thinks of. The international community focuses on the big issues but not on what it means to be on the ground, suffering every single miserable day.”

—Sam Totten

One of the men said, “We will not only rape you, but impregnate you with a child.” I told them, “Instead of raping me, it is better to kill me.” Immediately, one of the men hit me on the neck with a knife and ripped off my tob, and sliced off my underclothes with the knife and threw me to the ground and started raping me. The other women screamed and screamed. After all three had raped me, they took the cooking oil and poured it on the ground. Then one said, “You are rubbish! Get out of here.” As I got up, one said, “We could rape you anywhere. Even in your village.”

“There are so many people out there that nobody thinks of,” Totten said, when I asked him about the interviews. “The international community focuses on the big issues but not on what it means to be on the ground, suffering every single miserable day. So I flinch when people call me an expert on genocide. No. You’re not an ‘expert’ until you’ve lived through it.”

The Home Front

Totten knows about living in abject fear. When he was growing up in southern California, not a week passed when he and his younger brother were not beaten, whipped, choked or otherwise terrorized by his father, a policeman.

The elder Totten tore the house apart; held the family at gunpoint; broke his wife’s arm twice in a single evening; and meted out emotional abuse.

“Once I got a D in math,” Totten recalls. “He said, ‘I’m not gonna concern myself with your future, because I really think you’re mentally retarded.’”

Totten found respite in literature and earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in English. After teaching in Australia and Israel, he became a student in curriculum and teaching at TC to focus on educating about social issues.

He was influenced by Maxine Greene’s notion of “wide-awakeness” and Lawrence Cremin’s concept of the “configurations of education,” or the multiple ways, beyond the classroom, that people in a democratic society become educated. “That idea has driven what I’ve done throughout my career,” he says. “Careers” would be more accurate.

Over time, though, that balance shifted. When Totten wasn’t interviewing refugees or conducting research in the Nuba Mountains, he was in Rwanda, on a Fulbright, creating and teaching in a master’s degree program on genocide that enrolled members of Parliament and the Supreme Court. A few years ago, when a new department chair at Fayetteville told him to shelve his focus on genocide, he drew his line in the sand.

“I said, ‘This work is at the core of my being, and I’m not giving it up for you or for anyone,’” Totten recalls. Soon afterward, after more than 30 years on the university’s faculty, he left.

End Games

In mid-summer, Totten was in Fayetteville, scrambling unsuccessfully to salvage yet another mission to the Nuba Mountains. These trips require him to seek funders and supplement their contributions with his own money; find local “fixers” to contact the rebels and secure a vehicle; cadge last-minute rides on UN and cargo planes; and wangle letters of passage from rebel paramilitary organizations. This time, he would need to take an even more perilous route — up the Nile by boat, past potential ground fighting along both river banks (one on the Sudan side, the other on the South Sudan side). His biggest anxieties were possible actions of both the Government of South Sudan’s troops and rebel forces, which at this point, he says, are equally murderous and sadistic.

“I oscillate between being really geared up and thinking, ‘Is this how I want to die?’” he told me.

Totten’s missions have prompted even his admirers to accuse him of narcissism, of having a savior complex, and of selfishness toward those who worry about his safety. Kathleen Barta, his wife of 25 years, takes a different view.

“There are people who throw up their hands in a panic and say, ‘Somebody do something,’” Barta, a retired nursing professor, told me. “Well, Sam is that somebody. And when he commits, his follow-through is deep.

“People say, ‘Isn’t it time to stop?’ or ‘Let someone else take over.’ Well, who? If we all thought that way, where would the world be? So, no – as long as I’m ambulatory, I’ll continue.”

—Sam Totten

“He told me early on he wants to squeeze himself dry, until there’s nothing left,” she added softly. “I don’t want to say, ‘Don’t go out and do all this good for all these people,’ just because I’m afraid.”

Not long after that conversation, she sent me lyrics from a song called “Compassion,” by Lucinda Williams:

For everyone you listen to

Have compassion

Even if they don’t want it

What seems cynicism is always a sign

of things no ears have heard

of things no eyes have seen

You do not know

What wars are going on

Down there where the spirit

meets the bone

“That makes me think of Sam,” Barta wrote. “His heart’s so big, though he can have a tough exterior.”

Certainly Totten carries scars. He decided, decades ago, not to become a father, afraid that he carries too much anger. Not a day passes, he says, when he doesn’t think about genocide or berate himself for not doing enough. Ultimately, though, he believes his personal demons are beside the point.

“People say, ‘Isn’t it time to stop?’ Or ‘Let someone else take over.’ Well, who? If we all thought that way, where would the world be? So, no — as long as I’m ambulatory, I’ll continue, because I can’t stand the thought that I’m healthy and not helping the most desperate of the desperate. For me, that’s cowardice.”