Website editor’s note: Elie Wiesel was one of the three co-founders of the Institute on the Holocaust and Genocide in Jerusalem, together with Shamai Davidson, M.D., Director of the Shalvata Psychiatric Hospital, and a specialist in treating Holocaust survivors, and Israel W. Charny who has served as Executive Director of the Institute from 1982.

by Joseph Berger, International New York Times, July 2, 2016

Katie Rogers, Eli Rosenberg and Daniel E. Slotnik contributed reporting.

Elie Wiesel, the Auschwitz survivor who became an eloquent witness for the six million Jews slaughtered in World War II and who, more than anyone else, seared the memory of the Holocaust on the world’s conscience, died on Saturday at his home in Manhattan. He was 87.

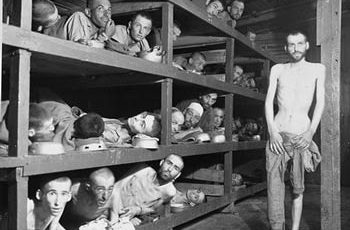

But by the sheer force of his personality and his gift for the haunting phrase, Mr. Wiesel, who had been liberated from Buchenwald as a 16-year-old with the indelible tattoo A-7713 on his arm, gradually exhumed the Holocaust from the burial ground of the history books.

Mr. Wiesel first gained attention in 1960 with the English translation of “Night,” his autobiographical account of the horrors he witnessed in the camps as a teenage boy. He wrote of how he had been plagued by guilt for having survived while millions died, and tormented by doubts about a God who would allow such slaughter.

Wiesel is in the second row of bunks, seventh from the left

“Never shall I forget that night, the first night in camp, which has turned my life into one long night, seven times cursed and seven times sealed,” Mr. Wiesel wrote. “Never shall I forget that smoke. Never shall I forget the little faces of the children, whose bodies I saw turned into wreaths of smoke beneath a silent blue sky. Never shall I forget those flames which consumed my faith forever. Never shall I forget the nocturnal silence which deprived me, for all eternity, of the desire to live. Never shall I forget those moments which murdered my God and my soul and turned my dreams to dust. Never shall I forget these things, even if I am condemned to live as long as God himself. Never.”

Mr. Wiesel went on to write novels, books of essays and reportage, two plays and even two cantatas. While many of his books were nominally about topics like Soviet Jews or Hasidic masters, they all dealt with profound questions resonating out of the Holocaust: What is the sense of living in a universe that tolerates unimaginable cruelty? How could the world have been mute? How can one go on believing? Mr. Wiesel asked the questions in spare prose and without raising his voice; he rarely offered answers.

“If I survived, it must be for some reason,” he told Michiko Kakutani of The New York Times in an interview in 1981. “I must do something with my life. It is too serious to play games with anymore, because in my place, someone else could have been saved. And so I speak for that person. On the other hand, I know I cannot.”

There may have been better chroniclers who evoked the hellish minutiae of the German death machine. There were arguably more illuminating philosophers. But no single figure was able to combine Mr. Wiesel’s moral urgency with his magnetism, which emanated from his deeply lined face and eyes as unrelievable melancholy.

“He has the look of Lazarus about him,” the Roman Catholic writer François Mauriac wrote of Mr. Wiesel, a friend.

President Obama, who visited the site of the Buchenwald concentration camp with Mr. Wiesel in 2009, called him a “living memorial.”

“He raised his voice, not just against anti-Semitism, but against hatred, bigotry and intolerance in all its forms,” the president said in a statement on Saturday. “He implored each of us, as nations and as human beings, to do the same, to see ourselves in each other and to make real that pledge of ‘never again.’”

Mr. Wiesel long grappled with what he called his “dialectical conflict”: the need to recount what he had seen and the futility of explaining an event that defied reason and imagination. In his Nobel speech, he said that what he had done with his life was to try “to keep memory alive” and “to fight those who would forget.”

“Because if we forget, we are guilty, we are accomplices,” he said.

A year earlier, on April 19, 1985, Mr. Wiesel stirred deep emotions when, at a White House ceremony at which he accepted the Congressional Gold Medal of Achievement, he tried to dissuade President Ronald Reagan from taking time from a planned trip to West Germany to visit a military cemetery there, in Bitburg, where members of Hitler’s elite Waffen SS were buried.

“That place, Mr. President, is not your place,” he said. “Your place is with victims of the SS.”

Mr. Reagan, amid much criticism, went ahead and laid a wreath at Bitburg. Paradoxically, the confrontation led to Mr. Wiesel’s first postwar visit to Germany. He said afterward that he had been extremely moved by the young German students he met and the depth of their painful search for an understanding of their country’s past. He urged reconciliation.

“Has Germany ever asked us to forgive?” Mr. Wiesel asked. “To my knowledge, no such plea was ever made. With whom am I to speak about forgiveness, I, who don’t believe in collective guilt? Who am I to believe in collective innocence?”

Mr. Wiesel had a leading role in the creation of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, serving as chairman of the commission that united rival survivor groups to raise funds for a permanent structure. The museum became one of Washington’s most powerful attractions.

“He was a singular moral voice,” said Sara J. Bloomfield, the museum’s director. “And he brought a kind of moral and intellectual leadership and eloquence, not only to the memory of the Holocaust, but to the lessons of the Holocaust, that was just incomparable. There is nothing that can replace the survivor voice — that power, that authenticity.”

Denouncing Persecution

In his 1966 book, “The Jews of Silence: A Personal Report on Soviet Jewry,” Mr. Wiesel called attention to Jews who were being persecuted for their religion and yet barred from emigrating. “What torments me most is not the Jews of silence I met in Russia, but the silence of the Jews I live among today,” he said. His efforts helped ease emigration restrictions.

Mr. Wiesel condemned the massacres in Bosnia in the mid-1990s — “If this is Auschwitz again, we must mobilize the whole world,” he said — and denounced others in Cambodia, Rwanda and the Darfur region of Sudan. He condemned the burnings of black churches in the United States and spoke out on behalf of the blacks of South Africa and the tortured political prisoners of Latin America.

Yet the plight of Jews was foremost. In 2013, when the United States was in talks with Iran about limiting that country’s nuclear weapons capability, Mr. Wiesel took out a full-page advertisement in The Times urging Mr. Obama to insist on a “total dismantling of Iran’s nuclear infrastructure” and its “repudiation of genocidal intent against Israel.”

Central to Mr. Wiesel’s work was reconciling the concept of a benevolent God with the evil of the Holocaust. “Usually we say, ‘God is right,’ or ‘God is just’ — even during the Crusades we said that,” he once observed. “But how can you say that now, with one million children dead?”

Still, he never abandoned faith; indeed, he became more devout as the years passed, praying near his home or in Brooklyn’s Hasidic synagogues. On the airplane that was to take him to an Israel darkened by the Arab-Israeli war in 1973, he sat shoeless with a friend, and together they hummed Hasidic melodies.

“If I have problems with God, why should I blame the Sabbath?” he once said.

Mr. Wiesel had his detractors. The literary critic Alfred Kazin wondered whether he had embellished some stories, and questions were raised about whether “Night” was a memoir or a novel, as it was sometimes classified on high school reading lists.

Mr. Wiesel blazed a trail that produced libraries of Holocaust literature and countless film and television dramatizations. While some of this work was enduring, he denounced much of it as “trivialization.”

What gave him his moral authority in particular was that Mr. Wiesel, as a pious Torah student, had lived the hell of Auschwitz in his flesh.

Eliezer Wiesel was born on Sept. 30, 1928, in the small city of Sighet, in the Carpathian Mountains near the Ukrainian border in what was then Romania. His father, Shlomo, was a Yiddish-speaking shopkeeper worldly enough to encourage his son to learn modern Hebrew and introduce him to the works of Freud. Later in life, Mr. Wiesel was able to describe his father in less saintly terms, as a preoccupied man he rarely saw until they were thrown together in Auschwitz. His mother, the former Sarah Feig, and his maternal grandfather, Dodye Feig, a Viznitz Hasid, filled his imagination with mystical tales of Hasidic masters.

He grew up with his three sisters, Hilda, Batya and Tzipora, in a setting reminiscent of Sholom Aleichem’s stories. “You went out on the street on Saturday and felt Shabbat in the air,” he wrote of his community of 15,000 Jews. But his idyllic childhood was shattered in the spring of 1944 when the Nazis marched into Hungary. With Allied troops fast approaching, many of Sighet’s Jews convinced themselves that they might be spared. But the city’s Jews were swiftly confined to two ghettos and then assembled for deportation.

“One by one, they passed in front of me,” he wrote in “Night,” “teachers, friends, others, all those I had been afraid of, all those I could have laughed at, all those I had lived with over the years. They went by, fallen, dragging their packs, dragging their lives, deserting their homes, the years of their childhood, cringing like beaten dogs.”

“Night” recounted a journey of several days spent in an airless cattle car before the narrator and his family arrived in a place they had never heard of: Auschwitz. Mr. Wiesel recalled how the smokestacks filled the air with the stench of burning flesh, how babies were burned in a pit, and how a monocled Dr. Josef Mengele decided, with a wave of a bandleader’s baton, who would live and who would die. Mr. Wiesel watched his mother and his sister Tzipora walk off to the right, his mother protectively stroking Tzipora’s hair.

“I did not know that in that place, at that moment, I was parting from my mother and Tzipora forever,” he wrote.

In Auschwitz and in a nearby labor camp called Buna, where he worked loading stones onto railway cars, Mr. Wiesel turned feral under the pressures of starvation, cold and daily atrocities. “Night” recounts how he became so obsessed with getting his plate of soup and crust of bread that he watched guards beat his father with an iron bar while he had “not flickered an eyelid” to help.

When Buna was evacuated as the Russians approached, its prisoners were forced to run for miles through high snow. Those who stumbled were crushed in the stampede. After the prisoners were taken by train to another camp, Buchenwald, Mr. Wiesel watched his father succumb to dysentery and starvation and shamefully confessed that he had wished to be relieved of the burden of sustaining him. When his father’s body was taken away on Jan. 29, 1945, he could not weep.

“I had no more tears,” he wrote.

On April 11, after eating nothing for six days, Mr. Wiesel was among those liberated by the United States Third Army. Years later, he identified himself in a famous photograph among the skeletal men lying supine in a Buchenwald barracks.

Only after the war did he learn that his two elder sisters had not perished.

A Postwar Mission

In the days after Buchenwald’s liberation, he decided that he had survived to bear witness, but vowed that he would not speak or write of what he had seen for 10 years. “I didn’t want to use the wrong words,” he once explained.

He was placed on a train of 400 orphans that was diverted to France, and he was assigned to a home in Normandy under the care of a Jewish organization. There he mastered French by reading the classics, and in 1948 he enrolled in the Sorbonne. He supported himself as a tutor, a Hebrew teacher and a translator and began writing for the French newspaper L’Arche.

In 1948, L’Arche sent him to Israel to report on that newly founded state. He became the Paris correspondent for the daily Yediot Ahronot as well, and in that role he interviewed Mr. Mauriac, who encouraged him to write about his war experiences. In 1956 he produced an 800-page memoir in Yiddish. Pared to 127 pages and translated into French, it then appeared as “La Nuit.” It took more than a year to find an American publisher, Hill & Wang, which offered him an advance of just $100.

Though well reviewed, the book sold only 1,046 copies in the first 18 months. “The Holocaust was not something people wanted to know about in those days,” Mr. Wiesel told Time magazine in 1985.

The mood shifted after Adolf Eichmann was captured in Argentina by Israel in 1960 and the wider world, in watching his televised trial in Jerusalem, began to grasp anew the enormity of the German crimes. Mr. Wiesel began speaking more widely, and as his popularity grew, he came to personify the Holocaust survivor.

“Night” went on to sell more than 10 million copies, three million of them after Oprah Winfrey picked it for her book club in 2006 and traveled with Mr. Wiesel to Auschwitz.

Mr. Wiesel wrote an average of a book a year, 60 books by his own count in 2015. Many were translated from French by his Vienna-born wife, Marion Erster Rose, who survived the war hidden in Vichy, France. They married in Jerusalem in 1969, when Mr. Wiesel was 40, and they had one son, Shlomo Elisha. They survive him, as do a stepdaughter, Jennifer Rose, and two grandchildren.

For Mr. Wiesel, fame did not erase the scars left by the Holocaust — the nightmares, the perpetual insecurity, the inability to laugh deeply. “I live in constant fear,” he said in 1983. In 2007, a 22-year-old man who called Mr. Wiesel’s account of the Holocaust fictitious pulled him out of a hotel elevator in San Francisco and attacked him. (The man was convicted of assault.)

From 1972 to 1976, Mr. Wiesel was a professor of Judaic studies at City College, where many of his students were children of survivors. In 1976 he was appointed the Andrew W. Mellon professor in the humanities at Boston University, and that job became his institutional anchor.

In an effort to promote understanding between conflicting ethnic groups, Mr. Wiesel also started the Elie Wiesel Foundation for Humanity. Through a synagogue acquaintance of Mr. Wiesel’s, it invested its endowment with the money manager Bernard L. Madoff, and his decades-long Ponzi scheme, revealed in 2008, cost the foundation $15 million. Mr. Wiesel and his wife lost millions of dollars in personal savings as well.

Mr. Wiesel lived long enough to achieve a particular satisfying redemption. In 2002, he dedicated a museum in his hometown, Sighet, in the very house from which he and his family had been deported to Auschwitz. With uncommon emotion, he told the young Romanians in the crowd, “When you grow up, tell your children that you have seen a Jew in Sighet telling his story.”